The division of property

On February 1st 1701, at the bequest of Pierre Jamme, a meeting was held of the friends and relatives of the Barbary family with Jacques Alexis Fleurye Deschambault then Lieutenant General, civil and criminal, for the area of Montreal. It was then agreed that Pierre Jamme would be the designated tutor of the Barbary minors, and Charles de Couagne would be the surrogate tutor. The two concessions (the one in Lachine, the other above Pointe Claire) belonging to Pierre Barbary, father, were evaluated. The estimated value minus deductions was divided by four; the share for each child was thus approximately two hundred and fifty "livres". Then, Pierre Jamme and his wife were granted the concession of Pointe Claire evaluated at two hundred "livres" plus the sum of fifty "livres" obtained from Pierre Barbary. The latter had inherited the house and the Lachine concession evaluated at eight hundred and fifty "livres": he agreed to pay his sisters Marie-Francoise and Marguerite "the sum of two hundred and forty-nine "livres" and ten "sols" (20 sols = 1 livre) plus interests, to each one of them, when they "returned" from the Iroquois and had reached maturity".

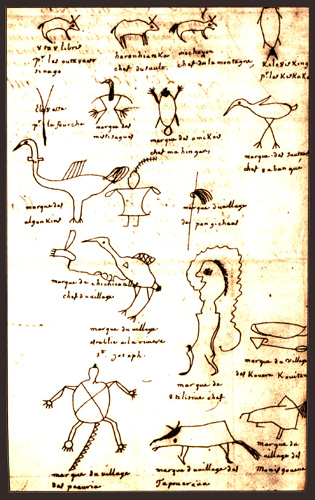

At the beginning of the summer of 1701, the discussions continued with the goal of a lasting peace treaty. In July, more than a thousand Indians belonging to about thirty tribes took part in the talks. The question of prisoner exchange, a long time stumbling block remained a delicate matter. Among the captives, some had been adopted and their new families did not want to return them; others did not want to return. In the end, Calliere persuaded all the interested parties to tackle the problem of making peace and to rely on his personal judgement to settle later each individual case to best of his ability. An agreement was thus reached and on August 4 1701, the peace treaty was finally signed.

During this time, the West Island was returning to life. The owners, absent from the area for fifteen years, were returning to work their land concessions. Pierre Jamme and his wife had inherited the one "above Pointe Claire" which Jean Tillard had undertaken to clear after his marriage to Marie, the eldest of the Barbary girls, but which had suffered from neglect over the years.

The two borrowed a hundred "livres" from Charles de Couagne "for goods and other necessities", rolled up their sleeves and got to work rebuilding their establishment and to raising a family. One year later, on April 7 1702, they extended their credit with Couagne for two hundred fifty-two "livres", six "sols" and eight "deniers" (12 deniers = 1 sol), " for balance of all accounts".

There was still no news of Marie-Francoise and Marguerite. Time had passed and the family had started to despair. In addition, Pierre Barbary who had married Francoise Paré one year after his return, believed that the agreement on the succession of his parents should be re-examined. According to him, the land concession of Lachine had been assessed too highly and he felt it should be adjusted to a lower value. He appealed to the Intendant Jacques Raudot.

In his decision, Raudot, concluded that there was really no more hope that Marie-Francoise and Marguerite would ever return; consequently, the inheritance should be divided into two rather than into four. Moreover, Pierre Jamme, ready to accept a lower estimate, offered, "to take for his share of the two said concessions, a third of the dwellings belonging to the said Barbary". With the approval of the two parties, the Intendant, Raudot issued an ordinance to this effect on June 14, 1707.

The family

The story of Pierre and Madeleine Jamme was now a happier one. This is not to say that their existence was easy and free from difficulties, but it was that of a family, that resolved problems as a family, a family that grew, in a climate of peace. Marie-Louise was born on September 28 1701, followed by Louis-Pierre who was born December 8, 1703. Marie-Anne saw the light of day on May 31, 1707 then Jean Baptiste, was born on March 2, 1710 but died one month later. Another son was born the following year, June 11 1711 and according to the custom of the time, was baptized with name of the baby who had died before, Jean Baptiste. Then, another son, Thomas was born. The church records of his baptism cannot be found because the registers of the parish of Lachine for this time period were destroyed by fire. It should be said that the Jammes had continued to live on the same land concession "above Pointe Claire" at a place today slightly inside the eastern border of Beaconsfield. Although they were part of the parish of "Notre-Dame-des-Anges" of Lachine, in winter, they baptized their children at "St-Louis-Haut-de-l"ile", located approximately four miles (7 kilometers) away. At other times, they went to Lachine, even though it was twice the distance to go there. The parish registers of Lachine are missing from December 1711 to January 1717; they are also missing from St-Louis-Haut-de-l'ile for the years 1712 and 1713. However in 1713, the parish St-Joachim of Pointe Claire was created and St-Louis-du-Haut-de-l'ile became Ste-Anne de Bellevue, where it appears there is a "bellevue" (beautiful view). When on September 20, 1716, the last of the Jamme children, Marie-Genevieve was born, it was in the new parish of Pointe Claire that she was baptized. She died young on March 17, 1718. In 1723, Louis-Pierre died, before his twentieth birthday.

The marriages of the remaining two sons and two daughters took place at St-Joachim of Pointe Claire. When the last one took place on November 26, 1731 between Thomas and Marie-Angelique Fauche, Madeleine Jamme had already passed away.

The End of an Era

On January 23 1735, Pierre Jamme had convened a meeting with Jacques Chasle dit Duhamel, an old comrade-in-arms of the De Cruzel company. In the presence of Jean Baptiste Adhemar, notary, of his two sons and of his two girls and their husbands, he said that he was getting quite old - he was then seventy-three year old - and unable to adequately work his property. He wanted a decision made on whom among them would take care of him for the remainder of his days and pay him a pension for life which would be paid by each child in turn. All agreed that Thomas was the best suited to care of their father and they all agreed to pay him "in good faith" the suggested pension. Pierre Jamme then made a donation of his land to his children. The eldest Marie-Louise and her husband Michel Brunet then gave up their right to the succession and all obligations for a sum of one hundred livres. Jean-Baptiste Jamme followed suit, with the same conditions but requested a sum of two hundred and sixty livres instead of a hundred. These sums were allocated at once. Pierre Jamme then affixed in an assured way his last signature on an official document: P. Jamme, with a paraphe.

On November 24 1740, H. Gladet, missionary priest signed in the church of St-Joachim of Pointe Claire the act of burial of "Pierre Jamme dit Cariere, who died the 22nd of the month, and was approximately seventy eight years of age".

Such is the story, tragic at times, of Madeleine Jamme and of her family, her parents, her husband, her brothers and sisters, her children.

It now remains to be told how the descendants of Pierre and Madeleine lived. We will write about Thomas, who inherited the land of his father, then of Jean, the son of Thomas. Each in turn, lived in the same area and worked establishing and developing new lands.

Then, there is the displacement of several of the sons of Jean including Joachim who went to a little corner of St-Benoit later called Ste-Scholastique, now Mirabel, in the county of Two-Mountains. A new fatherland not only for Joachim, but for his son, Thomas. Except for a short American interlude, it is also the native land of the son of Thomas, Damasse, my grandfather and that of my mother. It is a place to which I am very attached, even if I did not live there, except during holidays when I was a child.

Thank you Mr. Damasse Toupin for allowing us to know the life of our ancestors: Pierre Jamme and Marie-Madeleine Barbary.

Taking Action

The reprisals were quick in coming. On September 21, still in the year 1687, a colonist, Vincent Jean, living at the western end of the island, was killed. He had resided not far from the chapel of St-Louis, served by François d'Urfé. This Sulpician priest (a bay in the area now bears his name) had replaced Pierre Rémy. The latter had left "La Presentation", which had served the parishes of St-Louis and Lachine to become the pastor of Lachine alone.

Three days later, on the 24th, Levilliers, an ensign in the De Cruzel company, showed great courage in saving the life of a Basque officer, Amiconti, during an engagement with the Iroquois.

It should be remembered that the fort at "La Presentation" was the closest station of defence for the colonists isolated along Lake St-Louis to the west of the fort. The garrison was inevitably involved in all the Iroquois skirmishes in the area.

One week later, on September 30th, there was another raid. The victims were: Jean de Lalonde, Pierre Bonneau dit Lajeunesse, and Henri Fromageau, all three inhabitants of the west island, as well as Pierre Perthuis and Pierre Petiteau, probably soldiers in the De Cruzel company. On October 18th, there were new losses of life in the company: Pierre Camus dit Feuillade, Jean-Baptiste Lesueur dit Hogue, and Etienne Sorbet. On November 13th, there were even more casualties: the corporal Antoine Buissiere, Emery DuVerger, Antoine Lamplade and Gabriel Couteau. It was at this time that St Louis was abandoned.

Lacking sufficient manpower to subdue the Five Nations and worried by the war of attrition on the island of Montreal (and also at the forts Frontenac and Niagara which had been besieged), Denonville started peace talks. The Huron chief Kondiaronk, of Michillimakinac in the west, was a French ally, but he feared that such a treaty would bring a concentration of Iroquois forces against his own people.

He decided to take action. In the summer of 1688, having learned the location where a delegation of four Onondagas chiefs and forty warriors would pass on their way to Montreal to negotiate peace, he set up an ambush. One of the chiefs was killed, some men were wounded and the others were held captive. When the chief Teganissorens protested, declaring that they were ambassadors of peace, Kondiaronk, known as the Rat (not without reason) initially feigned astonishment. He then simulated a great rage against Denonville. He released them saying: "Go, my brothers, it is the French governor who made me do such a vile action that I will never be able to comfort myself, unless your Five Nations take a just revenge". During the months that followed, Kondiaronk continued with intrigues of this kind.

The peace negotiations were broken. The peace offerings were buried, signs of good faith, and war was brewing. A just revenge had suggested Kondiaronk. Proof would soon come that his words had been heeded.

The antecedents

Wars never prevented men from living and hoping for better days. Stationed at the fort of "La Presentation", Pierre Jamme was still a member of the de Cruzel company. Usually, each company was made up of 60 men; in the Carignan regiment, there were 66 at the time of their arrival in Canada. However, when they were at the small forts of the Lachine area - forts Cuillerier, Remy, Rolland, La Presentation - or other forts further away, they were usually made up of three to four officers and some twenty to twenty-five soldiers. This more closely resembles a Canadian platoon than a company. It is only later, around 1714, that the number of men was increased to forty.

The de Cruzel company having lost ten men since its assignment to "La Presentation" had suffered a loss of almost 50% of its manpower in six months. Pierre Jamme had a rather precarious career! According to some, the amused incredulity of Pierre Jamme towards his future prospects and the likely short duration of his career brought his comrades-in-arms to nickname him "La Carriere" which thereafter became "dit Carriere", "Carriere", "Carrieres" or "Cariere". This name ultimately supplanted his true name, "Jamme", which was written "Jeammes" also sometimes, "James" and even "Gemme". Isn't James an English name? Indeed it is a name with English resonance. It should be noted that Pierre Jamme was the son of the farm-laborer Jean Jamme and Marie-Charlotte Husse, of Lantheuil, diocese of Bayeux, in Normandy.

Lantheuil is a small borough of approximately 350 inhabitants. The church and the cemetery are adjoining. The tombstones are seldom more than a century old and the names generally do not have any significance for us, except for those of James and LeBourgeois. Michel LeBourgeois was witness to the burial of the three soldiers killed on October 18, 1687. The name of James is frequently found in the area and is probably of English origin, but is pronounced "Jamme" with the French accent and not "James" as we in North America would say it. For nearly four hundred years, France and England had fought over Normandy. One could even say that the Normans originally fought France and England. At the time of Pierre Jamme's birth, around 1662, this territory had been French for two hundred years. One should not be surprised, if in this province, the English had been frenchified, just like the French here had been able to be anglicized.

The marriage

Military career or not, Pierre intended to make a parallel career in his marriage. There was a lull with the Iroquois in the late fall of 1687. Pierre and Marie Madeleine Barbary decided to marry. At that time, a marriage contract constituted a major event. On October 24 1688 in front of the notary Jean-Baptiste Pottier of Lachine, appeared the future engaged couple with at least 10 witness: the father and mother of Marie Madeleine, several neighbors of the Barbary family, some comrade-in-arms such as Pierre Buisson who also belonged to the De Cruzel company from whom Pierre Jamme had obtained permission to marry. This contract foresaw the community of goods according to the Paris custom: the dowry of 300 "livres" (approximately $300), on behalf of Pierre Jamme to his wife and that of one heifer, two pigs, a half dozen hens and a cock from the Barbary parents.

It is not inappropriate here to mention a little about the Barbary family, otherwise known as Barbarin dit Grand'maison. Pierre Barbary, the father was originally from Thiviers in Perigord and arrived in Canada in 1665 as a soldier of the Carignan-Salieres regiment, Contrecoeur company. He took part in the construction of three forts on the Richelieu River, which was then called the Iroquois river and in a punitive mission undertaken by Mr. de Tracy at the Five Nations. With the disbanding of the regiment, he obtained a concession on the cote of St.-Sulpice that later became known as the cote of Lachine. On February 24 1668, he married Marie Lebrun originally from St-Jacques of Dieppe in Normandy. They had ten children including six girls. The eldest girl married Jean Tillard, became a young widow and remarried André Danis; the youngest married Pierre Jamme.

The year 1689 began well in Lachine. Three marriages occurred in eight days, in a population of approximately 300. This was certainly indicative of a certain optimism. On February 14, Jean Desforges, a soldier of De Lorimier joined in holy wedlock with Marguerite Verdon. On February 22, Jacques Denis of the De Cruzel Company married Marie-Anne Gaultier. Pierre Jamme was invited and present at both ceremonies. On February 21, Pierre, married Marie-Madeleine Barbary, then sixteen years old. Present at his wedding were Marie (Madeleine's eldest sister), officers of his company such as Charles de Caumartin sieur of Lantelle, Charles de Coulanges sieur De Levilliers as well as comrades-in-arms: Pierre Buisson, Jacques Denis and Jean Desforges. Neighbors and friends also present were: Jean Gourdon, Jean Michaud, Mrs. Jean Beaulne, Vincent Jean (son of the habitant of the same name killed in September 1687).

The Iroquois revenge

However, dark clouds were gathering. The rancor of the Iroquois was not appeased. On April 28, Anne, the five-year-old sister of Madeleine Barbary and Jean her three year old brother were kidnapped by the Iroquois and burned. They were buried three days later on May 1st 1689.

On May 7 1689, war broke out again between France and England. The Iroquois sure of the firearms support of their close English allies, gathered a strong force in order to attack and destroy the colony. On the nights of the 4th and 5th of August, under cover of a violent hail storm, approximately 1500 Iroquois attacked the 60 or so dwellings along the coast of Lachine avoiding the forts completely. The storm muffled the sounds of their movement and the blackness of the night hid them from view.

Just before dawn, the inhabitants were surprised in their sleep. Their homes were plundered and set afire, their animals killed. Men, women and children were massacred with such cruelty that one can hardly believe the accounts. It was such a carnage that the parochial register of the time referred to August 5 1689 as "the day of the destruction of Lachine". Among the victims, were found the bodies of the Michaud family, neighbors of the Barbary family, André Danis, the husband of Marie Barbary, the eldest daughter. Many were burned and could not be identified. The following day, according to Geodon de Catalogne, a historian and eyewitness, the attackers headed back "around 10 o'clock, we saw them go around the island of "La Presentation" as there was a well-manned fort there where three Iroquois were killed". They carried in their boats, spoils of war and prisoners, 90 according to Belmont and 120 according to Frontenac. The number is not significant. What is for us though is that Mr. and Mrs. Barbary and at least four of their children were amongst them, including Madeleine, the wife of Pierre Jamme, our ancestor.

What of Pierre Jamme? What happened to him? One must suppose that he was at the fort "La Presentation" where his company was garrisoned. Just like one must suppose that André Danis, his brother-in-law and soldier of the de Lorimier Company was on leave at his in-law's house. His body was found along with other civilians killed there. His wife was apparently not taken captive; she was presumed killed along with her husband even if her body was never identified.

As for Madeleine, she undoubtedly lived with her parents while her husband was on sentry-duty at the fort. Between their home (located not far from the town hall of Dorval) and the Barbary house (located not far from the town hall of Lachine), there was a distance of nearly five miles (8 kilometers) as the crow flies. In any event, nothing could have been done to intervene. All of the Barbary family had been kidnapped. Indeed, Barbary had ten children. Pierre, born in 1672 had died a little after his birth. Marguerite and Philippe born in 1675 and 1679 respectively are not mentioned in the census of 1681 and it should be presumed that they had also died young. Desire Girouard mentioned Philippe among the missing of August 5th, but he was probably wrong. If I allow myself a bit of humor, if only to cheer you up for a moment, I would say he was probably missing from 1681 and not from 1689. Thus there remained seven children: Marie, the eldest and wife of André Danis missing and probably killed along with him. Madeleine, the junior, married less than six months, to Pierre Jamme and brought into captivity by the Iroquois. Three other younger children were brought with her and the parents. There was Pierre, the fifth child, baptized with the same name as his deceased brother, then a little more than twelve years old, Marie-Francoise seven year old and finally Marguerite, born on May 31, then only two months. The two other children, Anne and Jean had already died at the hands of Iroquois three months earlier. The Iroquois guerrilla war continued around the Montreal area, although with less intensity, until the end of the autumn. Michel LeBourgeois, the comrade-in-arms of Pierre Jamme was killed on October 12, 1689.

The Counter offensive

On October 25, Frontenac asked to replace the weak Denonville, returned from France with Calliere. He immediately got to work, trying to raise the morale of the population devastated by the recent events in Lachine. He journeyed to the massacre site in order to evaluate the situation himself. Jacques Chasle Duhamel, another comrade-in-arms of Pierre Jamme, was married in the church of Lachine on December 2: de Cruzel and Frontenac were present.

Frontenac asked Iberville to organize a raid into the heartland of the English colonies. In February of 1690, Corlaer, now called Schenectady, was burned and destroyed, while the expedition from Trois-Rivieres devastated the village of Salmon Falls and the men from Quebec attacked Casco. "I don't see, Iberville said, the reason why we don't do to them what they've done to us in Orange (Albany) and in Manatte (New York) where they've provided arms and pay to the Iroquois to come kill the French of Montreal."

The English and Iroquois were in league together. In July, hard fighting occurred between the French and the Iroquois at Grou near "la rivière des Prairies". Laprairie, itself, was devastated in the autumn. Phips then attacked Quebec by sea. In the spring of 1691, the Iroquois attacked east of Montreal; then in August, Peter Schuyler, at the head of a troop of some three hundred soldiers and Indian allies fought at Laprairie de la Madeleine. In 1692, attacks were lead against Vercheres (where Madeleine saved the day). Lachenaie was also the object of an important raid. The skirmishes were so numerous, they could not be counted any more.

The enemy experienced many successes from 1689 to 1692, but in the final analysis the colony got the upper hand. In 1693, a detachment of 625 men struck a hard blow to the Mohawks in the Albany area. The Five Nations, then, started to separately negotiate peace with the French and their allies; they were hoping to divide them. The negotiations continued throughout 1694.

What was happening with the Barbary clan during this period? Five years had passed. Madeleine was now twenty-one years old, Pierre was seventeen, Françoise was twelve years old and Marguerite, five. With the Iroquois, it was a custom to preserve the life of children. Young people, when they were captured, were adopted into their own families and were then regarded as their own. This compensated them for their losses during wartime. As for the parents of the children, they had been (killed) burned, according to the expression of the time. This was something the French and their allies had done more then once to their own prisoners.

The Iroquois, Gagnyoton reported to Calliere, the governor: "My part in the Lachine affair was the taking of eight prisoners. I ate four of them, but the other four are alive. I do not know what the Onneiouts did with them...I repeat again that the Onondagas are the Masters of all the French prisoners". The exact fate of the Barbary parents is not known, but there is no doubt that their death was not an pleasant one.

Most of these events were partly known in the colony. In 1691, the Mohawks had returned all their prisoners; the following year, three prisoners were delivered to Cataracoui (Kingston) by Beaucourt and twelve were delivered to Long Sault but six escaped. In 1694, the Jesuit priest Pierre Millet, a prisoner with the Onneiouts since June 1689, brought back fifteen prisoners.

Face to face with all these events, Pierre Jamme must have been preoccupied with two dominant sentiments. Firstly, there was the hope of again seeing his wife whom he knew was a captive with his brother-in-law and his two sisters-in-law. Then, there was the desire for revenge that he shared with all the victims of this never-ending war. One can presume that he took part, if not as soldier of the Troops of the Marine at least in the militia, in a number of military engagements of this period. However, it is not easy to trace because the troops had been weakened by significant losses; orders were given to abolish seven companies and to incorporate the soldiers into the twenty-eight remaining ones.

In all probability, Pierre Jamme had continued the career that had given him his nickname. In February 1696, he attended the marriage of a comrade-in-arms of the Dumesnil Company, Pierre Sauve dit Laplante and Marie Michaud, a survivor of the unfortunate Michaud family, neighbours of the Barbarys.

Peace talks

The peace talks slowly progressed. The Iroquois tried to form an alliance with the Outaouais who were angry with their French allies because the latter were trading with their traditional enemies the Sioux and providing them with firearms. The Iroquois renewed their attacks. In July 1696, Frontenac launched a strong invasion of 2000 men and devastated the camps of the Onondagas and the Onneiouts who fled into the woods. Dumesnil controlled a battalion during this advance. It was the deathblow. In their weakened position, the Iroquois sought peace with a new eagerness. The exchange of the prisoners was in the centre of the talks, and almost caused their failure.

In 1697, the treaty of Ryswick restored peace between France and England. The Count of Bellamont the Governor of New York, demanded that the Five Nations bring the French prisoners to Albany to him so that he could give them back to the French; this implied that the Iroquois were allies of the English. For his part, Frontenac refused to recognize that the Five Nations were English allies, since this would have implied English control of their territories. He added that he would continue the war against the Iroquois if they, themselves, did not bring their prisoners to Montreal.

The situation became complicated due to the fact that many prisoners could not be returned. Teganissorens, an important Onondaga chief said: "We both took many prisoners during the war. Those that we took were given, according to our custom, to the families which had suffered looses during the war. It is not for us to return them. These families can give them back if they wish to; your people can do the same." Nevertheless, the talks resumed in 1698. This time, the Iroquois insisted that the tribes allied to the French be excluded from the treaty. The negotiations crawled along!

In July, another Dumesnil soldier, Pierre Pinau dit Larigueur was married. Pierre Jamme was present. The Governor-General, Frontenac, in Montreal for the negotiations, and Mr. Hauteville, the secretary of Mr. Calliere, were also present. I leave it to you to imagine what Pierre Jamme talked to them about during the reception! Frontenac died on November 28, 1698 and Calliere, hitherto the Governor of Montreal, replaced him as Governor of New-France.

The Exchange

In January 1699, the Onondaga chief, Ouhensiouan, accompanied by the Onneiout, Odatsigiita, came to Montreal in order to meet Governor Calliere. They wished to put an end to their war against the Indians in the West who were allied to the French. Calliere offered them peace offerings and was sympathetic, but nevertheless, he stated clearly that only an exchange of prisoners could put an end to the hostilities.

Hope was renewed. Pierre Jamme, to whom the calm of the last few months had provided a break, could now foresee the return of his loved ones and wanted to put his affairs in order.

The year before the attack on Lachine, a Jean Neveu had acquired from Pierre Barbary a land concession of 60 "arpents" located on Lake Saint-Louis or "au haut de l'ile", as the expression went, for the sum of two hundred and fifty "livres". He still owed a hundred and forty "livres" which he had been unable to pay because of the war; he could not work the land.

At the beginning of 1699, Pierre Rémy intervened by lending Neveu 37 "livres". He was his church caretaker, and he lent it to him on account as a sign of good faith. As for Jamme, he promised on his behalf as well as the other co-heirs, not to bother Neveu until he was well established on the said concession. Neveu promised to do so as soon as everyone in the area could also make their lands profitable".

During the summer - we are always in 1699 the Ouhensiouan and the Odatsighta, with the strong support of the Tsonnontouans, (that the English called "Senecas", a group of the Five Nations whose territory was the most westerly), returned to see Calliere who required a delegation more representative of the Five Nations.

On July 18 of the following year, the Ouhensiouan returned accompanied by Aradgi, another Onondaga chief and with four Tsonnontouans chiefs, notably Aouenano and Tonatakout. They claimed to speak in the name of the Five Nations, except the Mohawks. Calliere required that delegates of the Onneiouts and the Goyogouins be also present. Moreover it was agreed that the Jesuit father Jacques Bruyas, Chabert de Joncaire and Paul LeMoyne de Maricourt, all three greatly respected by the Iroquois, would accompany part of the delegation back to Onondaga, today Syracuse, in order to oversee the exchange of the prisoners.

The return

The group arrived at Onondaga at the beginning of August. A great feast was prepared for them. While waiting for the delegates of the nations that Calliere had requested be present, the three French ambassadors had the leisure time to converse with the prisoners. No effort was spared in order to repatriate them all, but few were persuaded. It should be said that the prisoners whether French or English, when adopted at a young age by the Indians, became attached to their new families who treated them with benevolence and kindness. These young people often preferred the Indian way of life.

The return voyage was organized. A delegation of 19 Iroquois representing the Five Nations, except the Mohawks arrived in Montreal on September 8. In their company were 13 French prisoners who were being released as a sign of good faith. The wife of Pierre Jamme, Madeleine Barbary Jamme, now a young woman of twenty-seven years of age and her brother Pierre, a young man of twenty-three, were amongst them. An eleven- years nightmare was over. A new era would begin. A sad note: Marie-Francoise and Marguerite were not among them.