This revolt occurred in both Upper and Lower Canada on the events that happened in Quebec.

In Lower Canada at this time, the leaders influencing government decisions were mainly wealthy English merchants and some rich Frenchmen. The majority of the population were French Catholic farmers. The interests of these two groups were quite different. Canals benefited the merchant class; taxes spent on building roads were more practical to farmers. The British Corn Laws in the 1820s -30s had favoured wheat producers in both Canadas. Things changed; more domestic production of wheat in England and Ireland created less demand for imported grain. This compounded by the agricultural crisis in wheat production in Lower Canada at the time lead to the impoverishment of many.

The leader of the French Patriots in the National Assembly was Louis-Joseph Papineau. From 1815 to 1837 he served as speaker. With great eloquence, he raised the population into open rebellion. Papineau and his supporters had drawn up 92 Resolutions, a list of political and economic reforms. When the British government rejected these, protest assemblies were held throughout Quebec. A radical

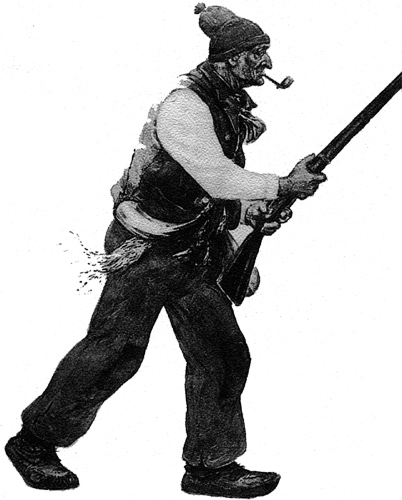

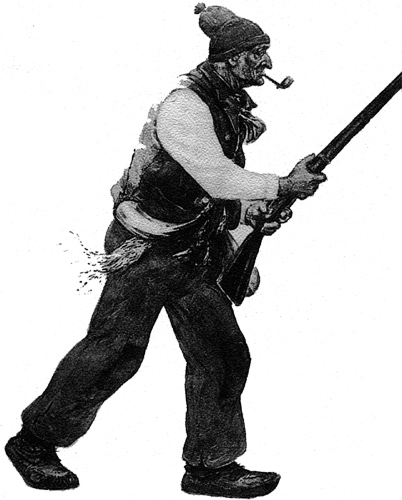

group of patriots formed an organization called the Fils de la Liberté. Several brawls occurred between the different factions. In November 1837 large-scale violence broke out. On the 18th, the Fils led by Brown seized the manor of Debartzch in Saint Charles. The British under the command of Wetherall headed for Chambly. At the Battle of St Denis the rebels were able to hold off an attack by British regulars and claim victory. On November 25, at the Battle of Saint Charles, Wetherall's forces attacked the Patriot army barricaded around the manor of Saint Charles. 28 Rebels were killed and 30 wounded while the British loses were seven dead and 23 wounded. The patriot forces were crushed after only 2 hours of fighting.

The British made a triumphal return to Montreal with many prisoners. Papineau fled to the United States. Martial Law was declared in Montreal.

The next clash occurred in St Eustache.

The convent of St Eustache had been set up as headquarters for the Patriots. Dr J.O. Chenier and others tried to drum up support in the surrounding area. The camp in St Eustache rapidly accumulated more then 1500 souls. Many of these went off to gather arms and ammunition for the coming conflict.

Meanwhile the English forces were organizing in St Martin. They readied for the orders of General John Colborne to go into action against the Patriots in St Eustache and the ones setting up camp in nearby St Benoit.

Once the alarm went off warning of the advancing English army, many of the Patriots searching for arms didn't return. Their numbers were now greatly diminished.

The English army advanced towards the small village on Thursday, December 14. it was at least 2000 men strong. it had eight pieces of artillery, rockets and 120 cavalry. Colborne had gained much military experience including the battle of Waterloo with Wellington against Napoleon.

The patriots at this point were less than 250 in the St Eustache camp. They were poorly armed. They occupied the church, the presbytery, the convent, the Dumont manoir - stone structures acting as barricades were their best protection against the enemy.

The English army marching in -14 F and 3 feet of snow surrounded the village. By 1:00pm they started to bombard the church with cannon fire. One by one , the stone houses occupied by the patriots were taken; then the convent and the presbytery were taken till all that remained was the church. The English failing to demolish the facade, ultimately set the church on fire. Chenier was killed. By 5:00 pm the battle was over. In reprisal, the village was burned. Without ceremony, the bodies of 11 patriots, including Dr Chenier were buried in unconsecrated ground beside the church.